Encouraging Students To Embrace Online Learning

Using AI to Teach AI in Duke’s MEng Program

Making humorous educational videos through an educator-comedian collaboration

by David Stolin

The beginnings

An educator and a comedian walk into a bar…

If this sounds funny, that’s probably because we don’t think educators spend much time around comedians. Yet when it comes to preparing top-quality online learning content, comedians are educators’ best friends.

This realization first struck me when I saw Sammy Obeid headline at a comedy club in California one April evening in 2018. (You may recognize Sammy as the host of the hit Netflix series “100 Humans”). Not only was he side-splittingly funny, but he held the tired, after-work audience in the palm of his hand even as he introduced mathematical concepts into his standup. I had been trying for some time to record online videos to support my classes, and by the end of the show, it was abundantly clear that I had much to learn from someone like Sammy.

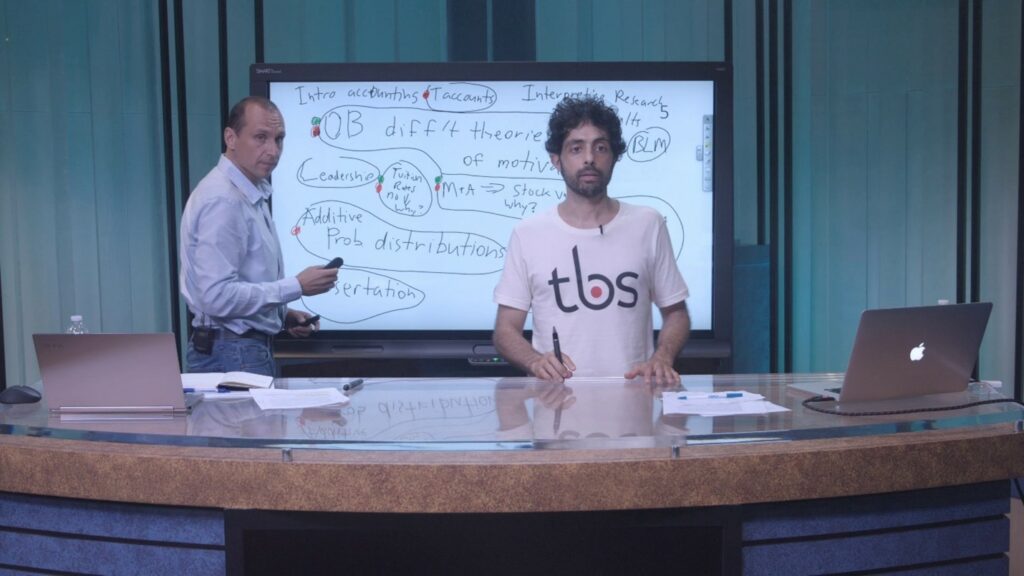

I reached out to him, and we began a collaboration that is continuing to this day. After very promising results on an initial home-made educational video, TBS Business School where I teach invited Sammy to Toulouse, France to collaborate with us in person (my colleagues and I describe the process in detail in Curran et al. 2020). As a result, over a dozen videos have been recorded to date, not only on finance (my own specialty) but also on international business, marketing, organizational behavior, and statistics and data science. This work has already received international recognition. The videos and the corresponding teaching notes are available from a dedicated webpage. For brevity (and fun), I will refer to such humorous educational videos as educational comedies, or edcoms – by analogy with situational comedies, or sitcoms.

Edcoms vs. sitcoms vs. educator humor

Sitcoms are widely used in teaching. To take economics as an example, according to Journal of Economic Education they include The Simpsons (Luccasen and Thomas, 2010), Seinfeld (Ghent, Grant, and Lesica, 2011), The Office (Kuester, Mateer, and Youderian, 2014), The Big Bang Theory (Tierney et al. 2016), Parks and Recreation (Wooten and Staub, 2019) and Modern Family (Wooten, Staub and Reilly, 2020). While the above articles refer to the approach whereby video clips from existing TV series (which were not conceived as educational tools) are matched to the most suitable learning outcomes, our approach is to start from the desired learning outcomes, and to inject professional-grade humor so as to facilitate their achievement. This allows one to have full control over which material is covered, focusing on the central message one is trying to convey, thinking deeply about the best way to communicate and highlight it by drawing on such staples of a comedian’s toolkit as metaphor, inversion, misdirection and repetition, and stripping away all the unnecessary verbiage to make the learning point (and the joke) as punchy as possible. The benefits of such embedded humor are many: it becomes an organic mnemonic device; it rewards learning through releasing “feel good” neurotransmitters; it tests learning in real time; and it can even result in the learner becoming the teacher if the only way to share the humor with others is through retelling the learning material in conjunction with the joke.

An even more commonly encountered use of humor in teaching is “amateur” humor by the instructor. This use of humor is important and will always have its place in face-to-face teaching. When it comes to pre-recorded educational videos, however, such humor is of limited value (Aagard, 2014). It is axiomatic that a collaboration between a professional educator and a professional comedian would result in a better integration of humor at the service of learning than either one could achieve on their own. Edcoms deploy professional-grade embedded humor as a weapon of mass instruction.

Embedding humor

Analogies are a key source of embedded humor, given how central they are to cognitive processing (Hofstadter and Sander, 2013). Here is Sammy using an analogy to explain why stock-picking is unlikely to be profitable for an individual investor: “There are a lot of professional investors who are competing with you for the same profit opportunities. They probably have better training, better resources and more money at stake than you. Going against them is like going against a professional MMA fighter, when you just shadowbox at the gym on Saturdays. It’s a dumb idea.”

What about other types of humor? There are numerous taxonomies, but one that I find to be particularly useful in practice is by Scott Dikkers (2014), the founding editor of The Onion. In addition to analogy, he lists ten additional humor “filters”: irony (saying the opposite of what you mean); character (a comedic character acting on his or her traits); reference (to something the viewer can relate to); shock (approaching or crossing the boundaries of what is seen as socially acceptable); hyperbole (exaggeration to the point of absurdity or impossibility); parody (comic imitation); wordplay (puns, rhymes, double entendres etc); madcap (silly and nonsensical humor); metahumor (humor about humor); and misplaced focus (putting emphasis on a minor fact instead of the central one). Not all of these filters are equally appropriate for edcoms. Shock should be used with extreme caution, and even then can backfire; wordplay humor may not work for non-native speakers; madcap and misplaced focus are likely to be distracting by definition; and metahumor is likely to require cognitive effort unconnected to achieving the learning objective (Mayer (2005) argues that such extraneous mental processing undermines learning). By contrast, the other five humor filters can play important supporting roles to analogy in embedding humor in edcoms, as illustrated below.

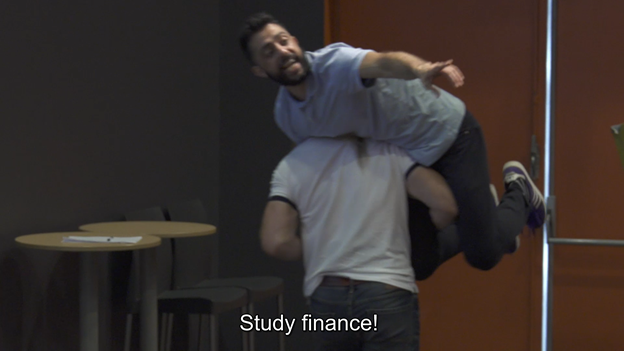

Hyperbole: “What is finance? It’s the management of money. You find some change on the ground, that’s finance.”

As Dikkers points out, more sophisticated and therefore more rewarding humor tends to use a combination of filters. As you keep working with a comedian, you should strive to set the bar higher by increasing the number of filters in a given joke.

Producing an on-demand edcom

Another way of setting the bar higher is by working on a challenging edcom topic, even if you are unfamiliar with it beforehand. This is what we did on August 9th, when Sammy and I gave an online workshop at the Academy of Management annual meeting. In it, we asked participants to propose to us a topic that their students struggle with, committing to record an edcom about it three days later. Now, the workshop received a fair amount of attention as it was a headline session and was voted the best session on teaching and learning, so we very publicly staked our credibility on the fact that one could take any topic and present it in a humorous way so that it is clear, memorable, and enjoyable to learn.

The topic that won out was Victor Vroom’s (1964) expectancy theory of motivation, something neither Sammy nor I had heard of before, although it turned out to be a standard topic in introductory courses on organizational behavior. After both of us read up on expectancy theory, an extensive consultation was held with the workshop participant who proposed the topic, which helped us understand the wider context in which the topic is typically presented, how it confuses students, and how it can be applied. At this point we decided to involve a recent psychology graduate who ended up guest-starring in the video and collaborating on scripting the video and preparing the corresponding teaching note (Mijangos and Stolin, 2020). We chose to structure our video as a (comically) brief presentation of expectancy theory, followed by two applications of it that presented humorous possibilities. Into this basic structure we incorporated humor; in fact, we used all eleven Dikkers (2014) humor filters, although madcap, shock and metahumor ended up in the outtakes, as shown and discussed in our “making of” video.

While I believe that the resulting edcom is successful – you be the judge – I would not attribute this to the topic being funny ex ante. During the workshop, we were not looking for an amusing topic, just for one that numerous students struggle with. Further, we did not find any particularly funny coverage of expectancy theory in any of the organizational behavior textbooks that we consulted, nor in videos explaining the theory. While the names of both the concept and its developer gave rise to wordplay humor in our edcom, it is generally not a problem to come up with wordplay or other humorous associations for any terms or names. Rather, I would argue that the combination of an experienced educator with an experienced comedian who are committed to working on making learning enjoyable is virtually guaranteed to result in an original, fun and insightful take on any topic – and the more you do it, the better you become at it.

An edcom manifesto

A short educational video with professional quality humor embedded into the learning material with the collaboration of a professional educator – what I call an edcom – may appear to be a rather esoteric product. Yet I believe edcoms have a key role to play in making education more effective.

Many learners are facing tough circumstances that make studying difficult not just logistically but also psychologically – and edcoms deliver a mood boost at the exact point it is most needed, i.e. when absorbing new material. Further, many learners come from educationally underprivileged backgrounds, and they will fall through the cracks unless they are ‘hooked’ both on a specific topic they are aiming to learn, and on learning in general – a role edcoms can play. Finally, many learners expend more effort and willpower in order to absorb and retain knowledge than needs to be the case – and edcoms help here, too.

A good question to ask oneself as an educator is: If my students have access to countless online educational resources prepared by my peers around the world, what is the best way for me to add value? A natural answer can be: offer them personalized instruction while curating existing resources, and incorporating the best ones into my class – hopefully including edcoms where available, for the reasons given above. But in parallel, creating one’s own edcom on a topic previously seen by learners as offputting is an amazing opportunity to help educate and engage a wider audience. It is also an opportunity to express oneself creatively and to grow as a teacher.

A good place to start is to read a book such as Dikkers (2014) that demystifies (at least somewhat) the process of writing a joke. The next step is to meet professional comedians – at a physical comedy club, or at one of many virtual ones (such as Sammy’s); you are likely to be surprised by how approachable, curious, smart, and open to trying new things and finding new audiences many comedians are. To explain the potential collaboration, simply show them this article. While access to a video recording studio is nice, it is not necessary for getting started. Much more important is identifying a topic that is in need of being more engagingly communicated, and then attacking it with creativity and enthusiasm. An effective, enjoyable first edcom will likely convince your organization to help you make more. And most importantly, keep collaborating. You will have a lot of arguments with your comedian partner about whether to prioritize pedagogy or humor – but as your collaboration progresses, you will be finding more and more synergies between the two, and will be discovering new insights into teaching even on topics that you have covered dozens or hundreds of times before.

So, what happens when an educator and a comedian walk into a bar? Find out for yourself… then set the bar higher.

References

Aagard, Hans P. (2014). The Effects of a Humorous Instructional Video on Motivation and Learning, Ph.D. Dissertation, Purdue University.

Allen, Michael W. (2016). Michael Allen’s Guide to e-Learning: Building Interactive, Fun, and Effective Learning Programs for Any Company (2nd edition), Wiley.

Banas, John A., Norah Dunbar, Dariela Rodriguez and Shr-Jie Liu (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research, Communication Education 60:1, 115-144.

Curran, Louise, Annalisa Fraccaro, Jessica Grandhomme, Elie Gray, Guilain Praseuth, Katia Santrisse, Roman Skripnik, David Stolin, Maxim Zagonov (2020). Injecting humor into educational videos: How a business school collaborated with a stand-up comedian. In Dan Remenyi (Ed), The 6th e-Learning Excellence Awards: An Anthology of Case Histories (pages 59-64). London: Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited.

Dikkers, Scott (2014). How to Write Funny: Your Serious, Step-By-Step Blueprint For Creating Incredibly, Irresistibly, Successfully Hilarious Writing, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Ghent, L. S., A. Grant, and G. Lesica (2011). The economics of Seinfeld, Journal of Economic Education 42(3), 317-18.

Hofstadter, D. and E. Sander (2014). Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, Basic Books.

Luccasen, R. A., and M. K. Thomas (2010). Simpsonomics: Teaching economics using episodes of The Simpsons, Journal of Economic Education 41(2), 136–49.

Martin, Rod A. and Thomas E. Ford (2018). The Psychology of Humor (2nd edition), Academic Press.

Mayer, R. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 31-48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mijangos, Briana and David Stolin (2020). Expectancy Theory of Motivation: A Teaching Note. TBS Business School. Available from https://tbs.bs/obeid.

Kuester, D. D., G. D. Mateer and C. J. Youderian (2014). The Economics of The Office, Journal of Economic Education 45(4), 392.

Tierney, J., G. D. Mateer, B. Smith, J. J. Wooten, and W. Geerling (2016). Bazinganomics: Economics of The Big Bang Theory, Journal of Economic Education 47(2), 192.

Vroom, Victor H. (1964). Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley.

Wooten, J. J. and K. Staub (2019). Teaching economics using NBC’s Parks and Recreation, Journal of Economic Education 50(1), 87-88.

Wooten, J. J., K. Staub & S. Reilly (2020). Economics within ABC’s Modern Family, Journal of Economic Education 51(2), 210.

About the author

David Stolin holds a PhD in Finance from London Business School, and has been a finance professor at TBS Business School since 1999. He conducts research on investment management, corporate governance and fintech, and has published in such outlets as Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, and Management Science.